Scratch a Russian boyar and you will find a foreigner! Sheremetevs, Morozovs, Velyaminovs...

Velyaminovs

The family traces its origins to Shimon (Simon), the son of the Varangian prince African. In 1027 he arrived in the army of Yaroslav the Great and converted to Orthodoxy. Shimon Afrikanovich is famous for the fact that he participated in the battle with the Polovtsians on Alta and made the largest contribution to the construction of the Pechersk temple in honor of the Assumption Holy Mother of God: a precious belt and the legacy of his father - a golden crown.

But the Vilyaminovs were known not only for their courage and generosity: a descendant of the family, Ivan Vilyaminov, fled to the Horde in 1375, but was later captured and executed on Kuchkovo Field. Despite Ivan Velyaminov’s betrayal, his family has not lost its significance: last son Dmitry Donskoy was baptized by Maria, the widow of Vasily Velyaminov, the Moscow thousand.

The following clans emerged from the Velyaminov family: Aksakovs, Vorontsovs, Vorontsov-Velyaminovs.

Detail: The name of the street “Vorontsovo Pole” still reminds Muscovites of the most distinguished Moscow family, the Vorontsov-Velyaminovs.

Morozovs

The Morozov family of boyars is an example of a feudal family from among the Old Moscow untitled nobility. The founder of the family is considered to be a certain Mikhail, who came from Prussia to serve in Novgorod. He was among the “six brave men” who showed special heroism during the Battle of the Neva in 1240.

The Morozovs served Moscow faithfully even under Ivan Kalita and Dmitry Donskoy, occupying prominent positions at the grand ducal court. However, their family suffered greatly from the historical storms that overtook Russia in the 16th century. Many representatives of the noble family disappeared without a trace during the bloody oprichnina terror of Ivan the Terrible.

The 17th century became the last page in the centuries-old history of the family. Boris Morozov had no children, and the only heir of his brother, Gleb Morozov, was his son Ivan. By the way, he was born in marriage with Feodosia Prokofievna Urusova, the heroine of V.I. Surikov’s film “Boyaryna Morozova”. Ivan Morozov did not leave any male offspring and turned out to be the last representative of a noble boyar family, which ceased to exist in the early 80s of the 17th century.

Detail: The heraldry of Russian dynasties took shape under Peter I, which is perhaps why the coat of arms of the Morozov boyars has not been preserved.

Buturlins

According to genealogical books, the Buturlin family descends from an “honest husband” under the name Radsha who left the Semigrad land (Hungary) at the end of the 12th century to join Grand Duke Alexander Nevsky.

“My great-grandfather Racha served Saint Nevsky with a fighting muscle,” wrote A. Pushkin in the poem “My Genealogy.” Radsha became the founder of fifty Russian noble families in Tsarist Moscow, among them the Pushkins, the Buturlins, and the Myatlevs...

But let’s return to the Buturlin family: its representatives faithfully served first the Grand Dukes, then the sovereigns of Moscow and Russia. Their family gave Russia many prominent, honest, noble people, whose names are still known today. Let's name just a few of them:

Ivan Mikhailovich Buturlin served as a guard under Boris Godunov, fought in the North Caucasus and Transcaucasia, and conquered almost all of Dagestan. He died in battle in 1605 as a result of betrayal and deception of the Turks and mountain foreigners.

His son Vasily Ivanovich Buturlin was the Novgorod governor, an active associate of Prince Dmitry Pozharsky in his fight against the Polish invaders.

For military and peaceful deeds, Ivan Ivanovich Buturlin was awarded the title of Knight of St. Andrew, General-in-Chief, Ruler of Little Russia. In 1721, he actively participated in the signing of the Peace of Nystad, which put an end to the long war with the Swedes, for which Peter I awarded him the rank of general.

Vasily Vasilyevich Buturlin was a butler under Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, who did a lot for the reunification of Ukraine and Russia.

Sheremetevs

The Sheremetev family traces its origins to Andrei Kobyla. The fifth generation (great-great-grandson) of Andrei Kobyla was Andrei Konstantinovich Bezzubtsev, nicknamed Sheremet, from whom the Sheremetevs descended. According to some versions, the surname is based on the Turkic-Bulgar “sheremet” (poor fellow) and the Turkic-Persian “shir-Muhammad” (pious, brave Muhammad).

Many boyars, governors, and governors came from the Sheremetev family, not only due to personal merit, but also due to their relationship with the reigning dynasty.

Thus, the great-granddaughter of Andrei Sheremet was married to the son of Ivan the Terrible, Tsarevich Ivan, who was killed by his father in a fit of anger. And five grandchildren of A. Sheremet became members of the Boyar Duma. The Sheremetevs took part in the wars with Lithuania and Crimean Khan, V Livonian War and Kazan campaigns. Estates in the Moscow, Yaroslavl, Ryazan, and Nizhny Novgorod districts complained to them for their service.

Lopukhins

According to legend, they come from the Kasozh (Circassian) Prince Rededi - the ruler of Tmutarakan, who was killed in 1022 in single combat with Prince Mstislav Vladimirovich (son of Prince Vladimir Svyatoslavovich, the baptist of Rus'). However, this fact did not prevent the son of Prince Rededi, Roman, from marrying the daughter of Prince Mstislav Vladimirovich.

It is reliably known that by the beginning of the 15th century. the descendants of the Kasozh prince Rededi already bear the surname Lopukhin, serve in various ranks in the Novgorod principality and in the Moscow state and own lands. And from the end of the 15th century. they become Moscow nobles and tenants at the Sovereign's Court, retaining Novgorod and Tver estates and estates.

The outstanding Lopukhin family gave the Fatherland 11 governors, 9 governors-general and governors who ruled 15 provinces, 13 generals, 2 admirals, served as ministers and senators, headed the Cabinet of Ministers and the State Council.

Golovin

The boyar family of the Golovins originates from the Byzantine family of Gavras, which ruled Trebizond (Trabzon) and owned the city of Sudak in Crimea with the surrounding villages of Mangup and Balaklava.

Ivan Khovrin, the great-grandson of one of the representatives of this Greek family, was nicknamed “The Head,” as you might guess, for his bright mind. It was from him that the Golovins, representing the Moscow high aristocracy, came from.

Since the 15th century, the Golovins had been hereditary treasurers of the tsar, but under Ivan the Terrible, the family fell into disgrace, becoming the victim of a failed conspiracy. Later they were returned to the court, but until Peter the Great they did not reach special heights in the service.

Aksakovs

They come from the noble Varangian Shimon (baptized Simon) Afrikanovich or Ofrikovich - the nephew of the Norwegian king Gakon the Blind. Simon Afrikanovich arrived in Kyiv in 1027 with a 3 thousand army and built the Church of the Assumption at his own expense Mother of God in the Kiev Pechersk Lavra, where he was buried.

The surname Oksakov (in the old days), and now Aksakov, came from one of his descendants, Ivan the Lame.

The word “oksak” means lame in Turkic languages.

Members of this family in pre-Petrine times served as governors, solicitors, and stewards and were rewarded with estates from the Moscow sovereigns for their good service.

On the same topic:

Morozovs and other most famous Russian boyar families The most famous Russian boyar families

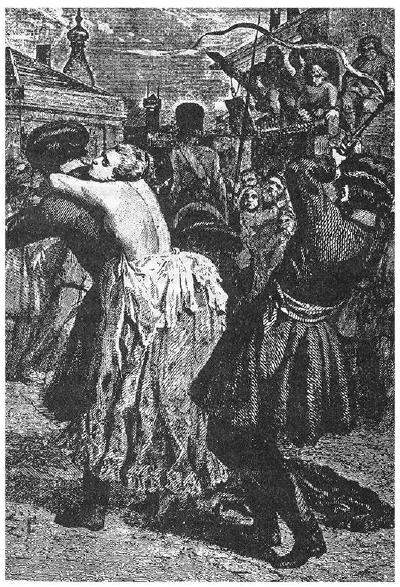

Her beauty was so dazzling that, as the folk legend says, when the soldiers were ordered to shoot her, for fear of seduction, they shot at her with their eyes closed, not daring even to look at her face. This information is not entirely accurate, although the execution did take place. In fact, no one shot, no one squinted, no one lowered their eyes. On the contrary, the spectacle-hungry crowd that thronged Vasilyevsky Island on August 29, 1743, looked with all their eyes at the scaffold, hastily knocked together from dirty boards, and at the menacing craftsmen with faces like udders, and at the impressive size of the bell that announced about the beginning of the execution. After reading the “most merciful” royal decree, which sentenced her to whipping, cutting out her tongue, confiscation of property and exile to Siberia, the executioner approached her, roughly tore off her mantilla and tore her shirt. She began to cry, trying in vain to snatch her dress to cover her nakedness. Here one of the executors imperiously grabbed her by the arms, turned and threw her onto his back, while the other inflicted cruel whistling blows of the whip on the victim one after another - one, two, three. After that, a new executioner approached the exhausted woman, either with pincers or with a knife in his hand. Unclenching the unfortunate jaw, he stuck the instrument into his mouth and with a swift movement tore out most of the tongue.

Who needs language? - he shouted with laughter, turning to the people, - Buy it, I’ll sell it cheap!..

How did this woman, Natalya Fedorovna Lopukhina (née Balk) (1699-1763), incur the royal wrath, and was dealt with as an inveterate state criminal? The answer to the question is given by her whole life, and therefore let us first turn to the pedigree of our heroine. According to her mother, Natalya came from a notorious Russian history the Mons family, from whom she inherited her remarkable beauty. Her aunt, the charming Anna Mons, as we already wrote, was for ten years the object of love of Peter the Great himself, and her uncle, the handsome and dandy Willim Mons, turned the head of Empress Catherine Alekseevna. However, they suffered cruelly from the eccentric king; Natalya’s mother, Matryona Mons (Balk), also got it, who was publicly flogged for indulging her brother and then expelled from the capital (and this despite the fact that at one time she was also Peter’s concubine). So Natalya Feodorovna, as the scion of a disgraced family, had reasons for persistent hatred of the Tsar-Transformer.

Natalya’s husband, Stepan Vasilyevich Lopukhin, who was the cousin of Peter’s first hateful wife, Evdokia Lopukhina, who was imprisoned by the Tsar in a monastery under “strong guard,” had a difficult relationship with Peter I. It was Peter, contrary to his declared decree not to force young people to marry, who literally insisted on Natalya’s marriage to Stepan, although they openly admitted that they did not experience the slightest attraction to each other. Stepan Lopukhin said later:

“Peter the Great forced us to marry; I knew that she hated me, and I was completely indifferent to her, despite her beauty.”

However, in the very first year of their marriage, the trial of Tsarevich Alexei broke out in Russia, during which the brother of Evdokia, who was languishing in the monastery, laid his head on the block, Abram Fedorovich Lopukhin; other representatives of the family ended up in distant Siberian exile.

The young couple was also injured. Modern historian Leonid Levin explained the reason for the persecution of Stepan: “There is a known episode that occurred in 1719, in the church during the funeral service for the son of Peter I from the second wife of Peter Petrovich, dearly loved by his father; standing at the child’s coffin, Lopukhin laughed defiantly and said loudly that “the candle has not gone out,” hinting at Peter’s only descendant in the male line - Pyotr Alekseevich - the son of the executed Alexei.”

For such a daring act, Stepan was put on trial, beaten by batogs and exiled together with his young wife to the White Sea, to Kola. But before his exile, he managed to get even with the informer, clerk Kudryashov, and mercilessly beat him up. Lopukhin was hot-tempered and boisterous, distinguished by his remarkable physical strength. Once in Kola, he literally terrorized the entire guard - he beat up the soldiers, and “he beat the sergeant on the head with a club and that club broke his, the sergeant’s, head.” The guards sent complaints to the capital one after another: “They beat and mutilated the soldiers so much that many almost died”; “Even an angel of God will not get along with him, and if you give him free rein, then in six months there will be no one left in prison.” He, like Natalya, burned Peter I, who dealt so harshly with his relatives. Omnipresent Secret Chancery ordered to beat the obstinate prisoner again with batogs, but he still did not let up.

Finally, the long-awaited will came, and the Lopukhins settled in Moscow, and with the accession of Peter II (that same “unextinguished candle”), they, like their other relatives, were returned to the Court. The “empress-grandmother” of the young emperor, Evdokia Lopukhina, with whom Stepan was friends, was given special honor.

The Lopukhins were also treated kindly under Empress Anna Ioannovna: they were given rich estates;

Stepan received the rank of general, and Natalya became one of the most prominent ladies of state of Her Majesty's Court, standing out for her desperate panache. This is how Valentin Pikul describes her preparations for going out: “I washed my white breasts with Danish water infused with cucumbers. The girls with handkerchiefs jumped up and began to wipe her breasts. Natasha washed her face with May milk from a black cow - for the sake of whiteness (already white). To make the step easier, I rubbed bitter almonds on my heels: there will be a fair amount of dancing. She glued a fly into the cut in the chest - a boat with a sail. She took out another one - with a heart, and - on her forehead! To indicate voluptuous languor, I drew blue arrows on my temples and realized that I was ready for love.” Lopukhina was known as a standard of beauty, a trendsetter of court fashions, and enjoyed resounding success in society. In addition to her irresistible beauty, the main charm of which was her dark and languid eyes, she was smart and educated. Her biographer, historian and writer of the 19th century Dmitry Bantysh-Kamensky enthusiastically wrote: “A crowd of admirers constantly surrounded the beautiful Natalya - with whom she danced, whom she honored with a conversation, he considered himself the happiest of mortals. Where she was not, forced gaiety reigned; she appeared - joy animated the company;... the beauties noticed closely what kind of dress she adorned, so that at least the outfit would resemble her.”

An interesting document has reached us. This is a register of a tailor, a certain Yagan Gildebrant, about work done but not paid for Lopukhina. Here the beauty is presented with an invoice: “For the work of the purple samara and for the butt of the bones, silk and dye - 3 rubles; for lacing work - 4 rubles; for the work of a fitted skirt and for attaching bones to it - 4 rubles; for the work of the made obyarinnova samara and for the butt of bones and silk; for the work of the orange-colored dreaming Samara and for the butt of it and silk.” We will not dwell on the specific details of clothing of that time mentioned here. Let us only note that Samara (or kontush) is, as costume historians write, “a child of the gallant age. wide clothes with a neckline, without a waist, falling in loose folds to the floor; a bodice was attached to it, which, although it outlined the bust, but only in front”; and a fizhbennaya was a skirt with bones or whalebone sewn into it. As for the color of the dress, our dandy apparently preferred bright colors, although she had long since passed thirty.

Another extraordinary beauty, the daughter of Peter I, Tsarevna Elizabeth, also shone at the Empress’s Court. According to the description of the wife of the English envoy, Lady Jane Vigor (Rondo), she had excellent brown hair, expressive blue eyes, healthy teeth and charming lips. She had an external polish: she spoke excellent French, danced gracefully, and was always cheerful and entertaining in conversations. In addition, Elizabeth was ten years younger than Natalya.

Beauty fans were divided into two camps - some gave the palm to Natalia, others to Elizabeth. Among the latter was Chinese Ambassador: when he was asked in 1734 who was the most charming woman at court, he pointed directly to Elizabeth. However, Lopukhina, who ruined, as a contemporary says, “a lot of hearts,” had much more adherents. Let us not become like the mythical Paris, who undertook to judge which of the beauties is better. Let us only emphasize that there was a long-standing rivalry between the ladies, who tried to outdo each other in every possible way. Competing with Elizabeth like woman with woman, Lopukhina, having found out what dress she was going to wear at the court or at the ball, could order the same dress for herself and appear in society in it, greatly irritating the ambitious princess. However, under Anna Ioannovna and, especially later, under the ruler Anna Leopoldovna, Natalya not only got away with such sensitive injections for Elizabeth, but also aroused ridicule of Peter’s daughter, who did not then enjoy much weight and influence. An additional incentive in this dandy battle was given to Lopukhina by her hatred of Peter, which passed on to his daughter. It seems that from then on Elizabeth also harbored a sharp grudge against Natalya Fedorovna.

For all their external dissimilarity, both ladies were the object of gossip. Natalya was called a “fornicating rascal,” and Elizabeth was also condemned for her “absent-minded life.” We will not give the names of the princess’s favorites, because she is not the heroine of our story. As for Lopukhina, in our opinion, she was condemned in vain. Yes, she was not faithful. But her marriage to her unloved man was doomed from the very beginning. By the way, Stepan Lopukhin also understood this - he did not reproach his wife for infidelity, but to some extent justified her, saying: “Why should I be embarrassed by her connection with the person she likes, especially since I need to give her justice, she behaves as decently as her position allows her.”

The dapper Chief Marshal, Count Reinhold Gustav Löwenwolde, became such a person for Natalya. “I owe my happiness to women,” they said about him. But it must be admitted that the long, time-tested disinterested relationship with Lopukhina did not add any titles or regalia to Reingold and was explained precisely by his heartfelt inclination. And although he could not be called a faithful lover (it was rumored that he kept a whole seraglio of Circassian beauties at home), the count was constant in his relationship with Natalya and opened up to her best sides of your nature. Lopukhina couldn’t even look at anyone except her dear Levenwolde!

She fully shared his political views. And the sympathies of Levenwolde and, accordingly, Lopukhina were on the side of the pro-Austrian party. This political orientation was followed by the Court of Anne of Brunswick, ruled by Vice-Chancellor Andrei Osterman, who liked to remain in the shadows. Among the welcome guests at the Court was the Austrian envoy Antonio Otto Botta d'Adorno, for whom Natalia and Reingold had deep respect.

In general, the time of Emperor Ivan Antonovich and the regent Anna Leopoldovna, who ruled for him, was golden for the Lopukhin family. Stepan Vasilyevich took the prominent post of General Kriegs Commissioner. Natalya Feodorovna also shone at the Court. And their son, Ivan Stepanovich, was appointed chamber cadet and accepted into the intimate circle of those especially close to the ruler. He also became friends with Anna Leopoldovna’s influential favorite, Karl Moritz Linar.

But the Lopukhins’ happiness collapsed overnight on November 25, 1741, when, as a result of a coup carried out by the guards of the Preobrazhensky Regiment, Elizaveta Petrovna came to power, and the Brunswick family was deposed and exiled. First of all, the new empress dealt with the leading dignitaries of the previous reign. The fate of Levenvolde, who was exiled to live forever in distant Solikamsk, was also tragic. The Lopukhins also fell into disgrace: the estates given by Anna were taken away from them. Stepan Vasilievich lost his position and was dismissed with the same rank, without any promotion or reward; Ivan Stepanovich was expelled from the chamber cadets (he was transferred as a lieutenant colonel to the army, without being assigned to a regiment); Natalya Fedorovna, although she continued to remain a state lady, felt the monarch’s dislike towards her.

But most of all, Lopukhina was depressed by the situation of her beloved Reinhold Gustav, for whom she passionately thirsted for revenge. And she took revenge on Elizabeth in a purely feminine way. Despite the ban on appearing at balls and in the palace in a dress of the same color as the empress, the headstrong lady of state dressed, as before, in an outfit not only of the same color, but also of the same cut. In addition, she decorated her hair with the same rose as Elizabeth's. This demonstrative disobedience to the royal prohibition was perceived as unheard of desperate insolence - the empress forced Natalya to kneel and, armed with scissors, cut the rose from her head and, in addition, whipped her on the cheeks. Such an outburst by Lopukhina was all the more unbearable for Elizabeth because, having become an autocratic empress, she no longer tolerated competition and praise of other people's beauty. And who, it would seem, would dare to compete with this crowned dandy? But Natalya Fedorovna dared, wanting to avenge her beloved! After the aforementioned scene, she completely stopped attending balls in the palace (later she would be reminded of this: “I didn’t go to the palace without permission.”).

Danger, however, crept up on the Lopukhins from another, unexpected direction. Looking ahead, let's say that they became one of the targets in the struggle between the courtiers and political parties, which unfolded at the Empress's Court. It all started with the fact that Natalya Fedorovna, having learned that a new bailiff, cuirassier lieutenant Yakov Berger, was going to the place of Reinhold Gustav’s exile, in distant Solikamsk, decided to send a message to her dear one. She instructed her son, Ivan, to convey her bow to the exile through Berger: “Count Levenwolde is not forgotten by his friends and should not lose hope, better times will not slow down for him!”

Holy naivety! The unscrupulous careerist Berger was just waiting for an opportunity to rise to the occasion at any cost, including a loyal denunciation. He immediately hurried to Elizabeth’s personal doctor, the influential Johann Hermann Lestocq, to whom he told Lopukhina’s exact words. Thanks to this, Berger’s appointment to God-forgotten Solikamsk was cancelled. He remained in St. Petersburg and was ordered to find out from Ivan Stepanovich on what the Lopukhins based their hopes that the fate of Levenwolde would change for the better. Berger, together with another informer, Captain Matvey Falkenberg, called young Lopukhin to a tavern, gave him a strong drink and began to eagerly listen to his drunken revelations. The family's bitter resentment towards the new government immediately spilled out. “The Empress goes to Tsarskoe Selo and takes bad people with her,” the intoxicated Ivan almost shouted, “she loves extremely English beer. She should not have been heir to the throne; She is, after all, illegitimate - she was born three years before her parents’ wedding. The current state rulers are all rubbish, not like the previous ones - Osterman and Levenwolde; Lestok alone is just a nimble rascal for the empress. Soon, soon there will be a change! My father wrote to my mother, telling me not to seek any favor from the current empress.” Provoking the talkative Lopukhin more than anything else, Falkenberg asked, as if by chance: “Isn’t there anyone else here?” And Ivan threw out the phrase, dear

cost the entire Lopukhin family: “The Austrian ambassador, Marquis Botta, a faithful servant and well-wisher to Emperor John.”

Having learned about the rantings of the younger Lopukhin, the “nimble rascal” Lestocq was inspired. His imagination painted an ominous picture of a total conspiracy against Elizabeth, the threads of which he, a physician devoted to the monarch, was called upon to unravel. What are the Lopukhins, when the enemy of the throne was a more important bird - the Austrian emissary Bott himself! However, he immediately remembered that Natalya was friends with Anna Gavrilovna (nee Golovkina, by Yaguzhinskaya’s first marriage), the wife of Mikhail Petrovich Bestuzhev. And her beloved brother of Anna Gavrilovna, Mikhail Gavrilovich Golovkin, like Levenwolde, was sent into Siberian exile, therefore, Bestuzhev is not favored by the new government. At the same time, she, like Lopukhina, was friendly with the Austrian marquis. But Anna Gavrilovna was not interested in Lestocq in and of herself, but only because she was the daughter-in-law of his main rival at the Court, Vice-Chancellor Alexei Petrovich Bestuzhev, who did not support his Franco-Prussian sympathies, but firmly pursued his political line towards an alliance with Austria. Thus, the ultimate task that Lestocq set for himself was to drag the vice-chancellor into the matter, overthrow him and thereby strengthen his influence on the empress.

And then everything seemed to go according to the plan developed by Lestocq. The first to be captured, thrown into a dungeon, and the talkative Ivan was interrogated with passion. On the rack, he confessed to everything and slandered his mother that the Marquis Botta came to her in Moscow and said: help will be provided to the Brunswick family. Under torture, Natalya Fedorovna also spoke. She admitted that the Marquis Botta visited her house more than once and talked about the fate of the august family. “I heard the words from him that he would not calm down until he helped Princess Anna,” Lopukhina answered, “and that’s why I told him not to make trouble and not make trouble in Russia. We had a conversation with Countess Anna Bestuzheva about Botta’s words, and she said that Botta said the same thing to her.”

Anna Gavrilovna Bestuzheva, also tortured, said: “I said not secretly: God forbid, when they (the Braunschweig surname) were released to their fatherland.” Stepan Vasilyevich Lopukhin, who was distinguished by his straightforwardness, was also called to the dungeon. He did not fuss, but immediately admitted: “That I am dissatisfied and offended by Her Majesty, I talked about this with my wife and the displeasure was such that. dismissed without rank; and for the princess [Anna Leopoldovna - L.B.] to be as before, I wanted so that with her I would be better.” He also confirmed that Botta spoke unflatteringly about the new empress and denounced the unrest of the current reign. Several more people were involved in this mythical “conspiracy”, which received the name “Lopukhin affair” in history - they were also punished for allegedly knowing about it, but not reporting it. According to Lestocq, Botta had to be the spring of the “conspiracy” - the life doctor directly told the interrogated people that if they pointed to the Marquis, their fate would be eased.

However, Lestocq's main goal - to eliminate Vice-Chancellor Alexei Bestuzhev - failed miserably. Even his brother, Mikhail Bestuzhev, married to the “state criminal” Anna Gavrilovna, was not harmed. She, Anna Bestuzheva, not only did not slander her husband, but completely whitewashed him.

The Russian Court insisted on exemplary punishment for Bott, about which Elizabeth wrote to the Empress of Austria-Hungary, Maria Theresa. The latter defended her emissary for some time, but then, not wanting to spoil relations with Russia, she sent him to Graz and kept him there on guard for a year.

The reprisal against the Russian defendants in the case was much more brutal. The General Assembly decided: Stepan, Natalya and Ivan Lopukhin, as well as Anna Bestuzheva, “having cut out their tongues, cut them on the wheels, put their bodies under the wheels.” However, Elizabeth, who swore that under her rule not a single death penalty would occur in Russia, commuted the sentence and granted them life. But what a life!

The exiles were taken to the most remote corners of Siberia. The place of settlement of Anna Bestuzheva is known - she was taken to Yakutsk, 8617 versts from St. Petersburg. Natalya Fedorovna also ended up in Yakutia, in the town of Selenginsk. She lived there for twenty long years. Deprived of her tongue, she could not speak and uttered a helpless moo, which only those close to her were able to understand. It is noteworthy that she, a German by nationality and a Lutheran by religion, while in exile, converted to Orthodoxy on July 21, 1757. What prompted her to do this? After all, the Russian God was so mercilessly strict towards her. Perhaps suffering enlightened her, and she accepted it as the salvation of her soul, as the highest grace.

With the accession of the Emperor Peter III Lopukhina received forgiveness and returned to St. Petersburg. The exaggerated “Lopukhin case” was revised. Here is what Catherine II wrote about him: “All this is a complete lie. Botta did not conspire, but he often visited the houses of Mrs. Lopukhina and Yaguzhinskaya; there they spoke somewhat unrestrainedly about Elizabeth, these speeches were conveyed to her; in this whole matter, with the exception of unrestrained conversations, not a trace of conspiracy is visible; but it is true that they tried to find him in order to destroy the great chancellor Bestuzhev, the brother-in-law of Countess Yaguzhinskaya, who married the brother of the great chancellor for the second time.”

In St. Petersburg, Natalya Fedorovna began to visit society again. But, Dmitry Bantysh-Kamensky summarized, “time and sadness have erased from the face the beauty that caused Lopukhina’s death.”

The biographer concluded that Elizabeth killed Natalya out of envy of her beauty. One thing is certain: the lady who dared to compete with the empress aroused indignation and hostility in the latter. Therefore, Elizaveta Petrovna was glad to deal with her when the opportunity presented itself.

Natalya Lopukhina outlived her abuser and left the world during the reign of Catherine II, on March 11, 1763, at the age of 64. IN recent years they no longer envied her beauty, no noisy crowd of admirers surrounded her, and no one believed that this faded, dumb old woman had once been a rival of the empress herself.

Lev Berdnikov

From the book “The Russian Gallant Age in Persons and Plots”, Vol.1

There are many examples in the history of painting when a particular painting has a trail of notoriety. Negative influence on the owners, the artist himself or the prototypes of the works defies logical explanation. One of these paintings is “Portrait of M. I. Lopukhina” by Vladimir Borovikovsky. In the 19th century. There were bad rumors about this portrait.

The daughter of retired general Ivan Tolstoy, Countess Maria Lopukhina, posed for V. Borovikovsky. At that time, she was 18 years old, she had recently gotten married, and this portrait was commissioned from the artist by her husband, the huntsman at the court of Paul I. She was beautiful, healthy and radiated calm, tenderness and happiness. But 5 years after the portrait was completed, the young girl died of consumption. During the time of A.S. Pushkin, there were rumors that if any girl just looked at the painting, she would soon die. As they whispered in the salons, at least a dozen girls of marriageable age became victims of the portrait. Superstitious people believed that the spirit of Lopukhina lived in the portrait, which took the souls of young girls to itself.

If we ignore the mystical component, one cannot fail to note the high aesthetic value of the portrait. This work is rightfully considered the pinnacle of sentimentalism in Russian painting and Borovikovsky’s most poetic creation. In addition to the undoubted resemblance to the prototype, this portrait is also the embodiment of the ideal of femininity in Russian art of the late 18th century. The natural beauty of the girl is in harmony with surrounding nature. This was the golden age of Russian portraiture, and Borovikovsky was considered its recognized master. A. Benois wrote: “Borovikovsky is so original that he can be distinguished among thousands of portrait painters. I would say he is very Russian."

The portrait of Maria Lopukhina delighted and inspired her contemporaries. For example, the poet Ya. Polonsky dedicated poetic lines to him:

She passed a long time ago, and those eyes are no longer there

And that smile that was silently expressed

Suffering is the shadow of love, and thoughts are the shadow of sadness.

But Borovikovsky saved her beauty.

So part of her soul did not fly away from us,

And there will be this look and this beauty of the body

To attract indifferent offspring to her.

Teaching him to love, suffer, forgive, be silent.

The painting owed its ill fame not to the author-artist, but to the father of the girl who posed for the portrait. Ivan Tolstoy was a famous mystic and master of the Masonic lodge. They said that he possessed sacred knowledge and, after the death of his daughter, “relocated” her soul into this portrait.

The rumors came to an end at the end of the 19th century. In 1880, the famous philanthropist Pavel Tretyakov purchased this painting for his gallery. Since then, it has been on public display for more than a century. Hundreds of people visit the Tretyakov Gallery every day, and no cases of mass mortality among them have been recorded. Talk about the curse gradually subsided and faded away. But people tend to believe in mystical coincidences: they say that the most expensive painting by Munch brings misfortune, and they list others

Many works known in painting are shrouded in mysticism, and sometimes even stories with bad fame. An example of such a work of art is the portrait of Maria Lopukhina. What is known about the author of this work and its features?

Story

The portrait of the young and beautiful Countess Maria Lopukhina, the eldest daughter of retired general Ivan Tolstoy, was painted by Russian portrait artist Vladimir Borovikovsky. This artist was known for his talented portraits of representatives of aristocratic society and icons. In 1795, the master depicted Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich, for which he was awarded the title of academician of painting.

Portrait of Maria Lopukhina

Another 2 years after this significant event, the master received an order for a portrait of eighteen-year-old Countess Maria Lopukhina. The order to paint the portrait was addressed to Borovikovsky by Mrs. Lopukhina’s husband, Jägermeister Stepan Lopukhin (he was 10 years older than his wife). In those days, parents chose future spouses for their children, and this marriage was concluded in the same way. There were rumors that neither Stepan nor Maria were happy in their marriage.

The author, with all responsibility and sympathy for the model, began to paint the portrait, and such sentiments of the author can be felt just by looking at the picture. If you look at Borovikovsky’s work, you may get the impression that the girl herself is posing against the backdrop of a park landscape, but in reality this is not the case. The background in the background is decorative, and the painting itself took place in the artist’s studio. By the way, the landscape background for painting portraits was characteristic feature the art of painting in the eighteenth century. As for this work, the author succeeded in high accuracy convey all the romanticism and beauty of the young model.

However, if you look closely at the expression on young Maria’s face, you can see on it a shadow of some sadness and, perhaps, impending trouble. As for the Countess herself, her life was cut short just 3 years after painting this portrait. A young woman at the age of 21 literally burned out from consumption, without having time to acquire heirs. By the way, Stepan Lopukhin himself also died shortly after his wife.

Mysticism

In connection with the tragic fate of Maria Lopukhina, the portrait in which V. Borovikovsky depicted her was shrouded in numerous unpleasant mystical stories. In the time of Pushkin, it was believed that if a young unmarried girl looked at this picture, she herself would soon die from terrible disease. There were rumors that the portrait was fatal for more than a dozen young beauties.

Another mystical story is connected not only with Maria herself, but also with her father, who during his lifetime was the master of the Masonic lodge and the owner of occult knowledge. There was a version according to which Ivan Tolstoy, after the early death of his daughter, “endowed” the famous painting with her spirit.

However, in 1880 all the rumors and scary stories about Borovikovsky’s work were nullified after the portrait of Countess Lopukhina was bought by the philanthropist P. Tretyakov. The painting was exhibited in his gallery, which was eventually called Tretyakov Gallery. Since then, millions of people have seen this famous portrait live, but, fortunately, not a single death from viewing the painting has been recorded. Today, the portrait of Countess Lopukhina is still on display at the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

Family of the Most Serene Princes Lopukhins-Demidovs. Part 1.

Coat of arms of His Serene Highness Prince Nikolai Lopukhin-Demidov

The family of the Most Serene Princes Lopukhin-Demidov appeared in Russia in 1873 after the death of the childless Most Serene Prince Lieutenant General Pavel Petrovich Lopukhin, who, by the Highest Decree, was allowed to transfer his surname and title after his death to the grandson of his elder sister Nikolai Petrovich Demidov.

His Serene Highness Prince Pavel Petrovich Lopukhin (1788 - 1873). Miniature of the work of an unknown author

His Serene Highness Prince (since 1873) Nikolai Petrovich Lopukhin-Demidov

The Lopukhin and Demidov families became related in 1797 as a result of the marriage between the aide-de-camp of the Second Captain of the Life Guards Cavalry Regiment, the son of the owners of iron factories in the Urals, Grigory Aleksandrovich Demidov, and Ekaterina Petrovna Lopukhina - the sister of Pavel Petrovich and the daughter of Pyotr Vasilyevich Lopukhin, a former general -Governor of Yaroslavl and Vologda, whom Paul I shortly before ordered to be present in the Moscow Department of the Government Senate. Later G.A. Demidov was a court councilor of the foreign board, a chamberlain, and an actual chamberlain.

Grigory Alexandrovich (1767-1827), since 1797 married to Princess Ekaterina Petrovna Lopukhina (1783-1830).

Ekaterina Petrovna Demidova, née Lopukhina, unknown artist

In origin, the groom's clan was much lower than the bride's clan. Grigory Aleksandrovich Demidov was a fifth-generation descendant of the famous blacksmith, who received the title of nobility from Peter I.

Naumkin Victor. Peter 1 in Tula

The Demidovs at a reception with Peter I, Kostylev Sergey

The Lopukhins descended from the legendary Kasozh prince Rededi, who owned Tmutarakanyu, who was killed in 1022 by Mstislav, the son of Grand Duke Vladimir, who baptized Rus'. There was a legend that Rededi’s son, Roman, married the daughter of Mstislav Vladimirovich. After another eight generations, Vasily, nicknamed Lopukha, appeared in this family, giving the name to the Lopukhin family, to the eleventh generation of which P.V. belongs. Lopukhin. Evdokia Lopukhina, the first wife of Peter I, belonged to another branch of this family.

Painting by N.K. Roerich "Martial arts between Mstislav and Rededya"

Ivanov Andrey Ivanovich. Martial arts between Prince Mstislav Vladimirovich Udaly and the Kosozh prince Rededey 1812

His Serene Highness Prince Pyotr Vasilievich Lopukhin (1753-1827)

Praskovya Ivanovna Lopukhina, ur. Levshina (175.-178.), first wife of St. Prince P.V. Lopukhin, had three daughters in marriage, one of them was the famous favorite of Paul I - Anna Petrovna Gagarina, ur. Lopukhina.

Lopukhina Ekaterina Nikolaevna (Highest Princess) second wife of Pyotr Vasilyevich Lopukhin, mother of his only son, Pavel Petrovich

The bride Ekaterina Lopukhina had just turned fourteen years old, and she was not indifferent to the heir, Tsarevich Alexander, which greatly bothered him. She was married to G.A. Demidov, who was eighteen years older than her. They lived on the corner of Moika and Demidov Lane, in an estate built by Grigory Alexandrovich’s grandfather, Grigory Akinfievich. The famous memoirist F.F., who visited this house. Wigel recalled that he met with Demidov and “his young, beautiful, melancholic wife, whom her husband was jealous of the whole world.”

Soon after the wedding, favors rained down on the Lopukhin family. At a ball in Moscow, Emperor Pavel saw Lopukhin's other daughter, Anna, who soon became his favorite. Big role In this story, Paul’s permanent favorite, former barber, and then Count I.P. played. Kutaisov, by the way, married his son Pavel to another daughter of Lopukhin, Praskovya.

Pavel I, Andrey Filippovich Mitrokhin

Anna Petrovna (1777-1805) and Ekaterina Petrovna Lopukhin (1783-1830), George Henry Harlow

Ivan Pavlovich Kutaisov

Kutaisov Pavel Ivanovich (1780-1840), chamberlain, honorary commander of the Order of Malta.G. Chernetsov.

Praskovya Petrovna Kutaisova, née Lopukhina (1784—04/25/1870)

In 1798, Paul I translated P.V. Lopukhin to St. Petersburg, appointing him Prosecutor General of the Senate. Soon he became an active Privy Councilor, a member of the State Council, and received, in addition to the already existing ones, the Order of St. Andrew the First-Called. And all this in the last five months of 1798. In January 1799 he became Commander of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem.

His Serene Highness Prince Pyotr Vasilyevich Lopukhin (1753-1827), Vladimir Borovikovsky

January 16, 1799 P.V. Lopukhin received a huge estate for eternal and hereditary possession - the eldership of Korsun in the Kyiv province, which gave an annual income of 200 thousand rubles. It was bought for the treasury from the nephew of the Polish king, Prince Stanislav Poniatowski, for 600 thousand zlotys (10 thousand rubles in silver). The decree stated that the complainant was the town of Korsun with all the villages, lands, lands, garden and castle, as well as furniture, marbles, a library, and dishes. Now this is the city of Korsun-Shevchenkovsky.

Korsun, Napoleon Orda

Angelika Kaufman. Portrait of Prince Stanisław Poniatowski, 1788

On January 19, 1799, Paul I issued a decree: “As an undoubted sign of Our royal favor and as a reward for the fidelity and zeal in the service of our actual Privy Councilor, Prosecutor General Lopukhin, We have most mercifully granted him the Prince of Our Empire, extending this dignity and title to all his descendants , Lopukhina, what’s happening.” And on February 22 of the same year " Prince Lopukhin and his entire family were granted the title and privilege of His Serene Highness» .

In the newly created coat of arms of the Most Serene Princes Lopukhins, in the lower part of a horizontally divided shield on a silver field there was depicted a red vulture taken from the shield in the coat of arms of the Lopukhins nobles, and in the upper part on a golden field - “a black double-headed eagle, crowned, on the chest of which the name of the Sovereign Emperor is depicted Pavel Pervago." Under the shield is the motto “ Grace" The motto was not chosen by chance: the name Anna translated from Hebrew means “ grace b".

Veil Jean-Louis Anna Petrovna Lopukhina

It is possible that Grigory Aleksandrovich Demidov was obliged to receive the title of chamberlain because he was the son-in-law of His Serene Highness Prince Lopukhin.

We should pay tribute to Pyotr Vasilyevich Lopukhin. It was not only thanks to his daughter that he reached the highest positions in the state. He was a smart man and served well. Later, under Alexander I, he was Minister of Justice, chaired various departments of the State Council, and then was chairman of the State Council and the Committee of Ministers. Pyotr Vasilievich Lopukhin died in 1827.

Shchukin Stepan Semenovich. Portrait of Pyotr Vasilyevich Lopukhin. 1801

After his death, the title of Most Serene Prince passed to his only son Pavel Petrovich (1788-1873), who participated in all the wars with Napoleon and in the Polish campaign. He rose to the rank of lieutenant general, retired in 1835 and settled on his estate Korsun. He was married to Zhanetta Ivanovna, Dowager Countess Alopeus, and had no children.

Korsun on a Polish engraving

Countess Jeanette (Anna Ivanovna) Alopeus (1786-1869), born. Baroness von Wenkstern, wife of diplomat D. M. Alopeus, in her second marriage to Prince P. P. Lopukhin.

Artist Friedrich Johann Gottlieb Lieder

Zhanetta (Anna) Ivanovna Lopukhina (1786-1869), born. Baroness von Wenkstern, 1st marriage to Countess Alopeus, 2nd marriage to Prince P.P. Lopukhin.

Artist Karl Bryullov

In 1863, Pavel Petrovich, who was 75 years old at that time, decided to take steps to ensure that the line of the Most Serene Princes Lopukhins did not fade away. To do this, he decided to ask for the establishment of a majorate in his estate of Korsun, Boguslavsky (later Kanevsky) district of the Kyiv province and to petition for “permission to transfer his surname with the title to his elder sister’s own grandson, captain Nikolai Petrovich Demidov.”

He submitted a most loyal petition to Emperor Alexander II: “ Your Imperial Majesty! My parent, His Serene Highness Prince Peter Lopukhin, continued for 66 years his infinitely diligent and always excellent service to your six august ancestors Imperial Majesty and had the good fortune to earn the attention, power of attorney and favors of Catherine II, Paul I, Alexander I and your Great Parent Nicholas I<…>I am the only son of my parent, lived to a ripe old age and have no direct descendants»

Portrait of Alexander II. 1856, Botman Egor Ivanovich.

In 1864, the captain of the Cavalry Regiment, Nikolai Petrovich Demidov, himself submitted a petition to transfer the surname and title of his great-uncle to him. He writes that “a primacy was established over the estate of the princes Lopukhins, about which a case was made in the Ministry of Justice, in which there are proper documents proving my descent from the princes Lopukhins through the female line.” It also required the consent of his mother, Elizaveta Nikolaevna Demidova, née Bezobrazova, for him to adopt his surname and title (Nikolai Petrovich’s father, Pyotr Grigorievich, died in 1862).

Pyotr Grigorievich (1807-1862), to his son Nikolai, after the death of his grandmother’s childless brother, Prince P. P. Lopukhin, in 1873 the princely title was transferred and he was allowed to be called “Demidov, His Serene Highness Prince Lopukhin,” so that the surname this was assigned only to the eldest in his family.

In 1866, the opinions of the Department of Heraldry of the Governing Senate, the Ministry of Justice and the State Council were collected. It was decided that the grandson of Ekaterina Petrovna Demidova, nee Lopukhina, is no longer a captain, but Lieutenant Colonel Nikolai Demidov “is the closest relative of Lieutenant General Prince Lopukhin, and since there are no other close relatives of the Lopukhin family, then by virtue of paragraph 1 of Art. 57 of volume IX of the law of 1864, Prince Pavel Lopukhin has the right to transfer his surname with the coat of arms and title to Nikolai Demidov.

Ekaterina Petrovna Demidova, née Lopukhina, artist Thomas Lawrence

Generally speaking, the statement that there were no other close relatives of the Lopukhins family is somewhat controversial. Mikhail Lopukhin was alive, whom Pavel Petrovich, bequeathing his Pskov estate to him, calls the great-grandson of his grandfather. It is likely that this Mikhail Lopukhin, unlike Nikolai Demidov, was not a direct descendant of His Serene Highness.

It should also be noted that by 1863 more than one grandson of Catherine Petrovna was alive, who, by the way, having married early, did not have time to be the Most Serene Princess, although in all later documents she is usually called that way.

Nikolai Petrovich's brother Grigory died early, but four cousins were alive - the sons of his father's brothers: Pavel Grigorievich and Alexander Grigorievich, who was older. The latter's son, Alexander Alexandrovich, not only belonged to the eldest branch, but was also older in age than Nikolai Petrovich, who for some reason was called the eldest grandson. Why was the son of the middle brother, Pyotr Grigorievich, chosen as the heir to the family name and title?

Portrait of Emperor Nicholas I, Franz Kruger

Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna of Russia, Duchess of Leuchtenberg, Franz Xavier Winterhalter

Perhaps it also played a role that the eldest grandson, Alexander Alexandrovich, had already retired due to illness as a staff captain, and military service was very much valued.

On January 17, 1866, permission from the emperor was received: “ We, in accordance with the most submissive petition of Lieutenant General His Serene Highness Prince Pavel Petrovich Lopukhin and the opinion of the State Council, which was approved by Our approval, based on the conclusion of the Governing Senate, We most mercifully allowed him Colonel Demidov, as the closest relative of the petitioner, to add to his family name the surname and title of His Serene Highness Prince Lopukhin and be called Prince Lopukhin-Demidov<…>so that: 1) such appropriation does not change the order of inheritance of family property,

2) the indicated surname and title to him not before, as after the death of the last representative of the princely surname of the Lopukhins, Lieutenant General Prince Lopukhin, and when the latter has no male descendants."

Princes Lopukhins - Pyotr Vasilyevich and his son Pavel Petrovich - owners of the Korsun estate (1799-1827, 1827-1873). Family coat of arms of the princes Lopukhins

Since the elderly Prince Lopukhin never had any descendants, after his death in 1873, on May 30 of the same year, it was ordered that Nikolai Petrovich Demidov and of his descendants always only the eldest in the clan “be named both in writing and in words All-Russian Imperial Princes with the annex “The Most Serene”, and both in ours and in foreign countries, received all the rights, privileges and benefits that befit and belong to that dignity.” “We always favor him and his descendants only to the eldest in the clan and in all cases unquestioningly allow us to use the following combined coat of arms of the surnames of the Most Serene Princes Lopukhins and the Demidov nobles.” The coat of arms has a four-part shield with a small shield in the middle, in the golden field of which there is black double headed eagle, on his chest is the monogram of Paul I. In the first and fourth parts of the shield is the coat of arms of the Lopukhins nobles: a red vulture in a golden field. In the second and third parts - the coat of arms of the Demidov nobles: in the upper part, in a silver field, three green mining vines, in the lower part - a silver hammer in a black field. The shield is topped with three helmets: the middle one with a black double-headed eagle with the monogram of Alexander II, the right one with the Lopukhins emblem - seven ostrich feathers, the left one with the Demidovs emblem - a hand with a hammer. Shield holders: on the right - the goddess Themis with scales, on the left - a warrior with a crimson banner. The shield is covered with a princely mantle and crowned with a princely cap. Below is the motto: “God is my hope.”

The Kiev Noble Deputy Assembly included His Serene Highness, Colonel Lopukhin-Demidov, in the 5th part of the Noble Genealogy Book, where representatives of titled families were recorded. His children, just like the Demidovs, not princes, remained in the 1st part.

To be continued.....